Telling a Kelvin Soldier’s Story

November 14, 2022

When it comes to the First and Second World Wars, École secondaire Kelvin High School has a sizeable list of alumni who lost their lives.

Within that tragic history are many fascinating stories. Kelvin student Uday Bhardwaj had the opportunity to travel to France to tell the story of one of those men: Alexander Logan Waugh.

The son of Winnipeg Mayor Richard Deans Waugh, Alex had an affinity for writing and became a member of the Canadian Machine Gun Corps during the First World War. He ultimately died in France on Dec. 1, 1917, after being shot by a German sniper.

Uday had the opportunity to tell Waugh’s story to fellow Canadian students, just a short distance from where the soldier died all those years ago.

The trip was made possible by The Vimy Foundation, in partnership with Scotiabank and Air Canada.

Prior to Uday’s trip to Vimy, WSD had the opportunity to interview the student about his research and this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Q: How do you feel about being selected for the Vimy Pilgrimage?

Uday: I feel absolutely ecstatic. I'm getting a once in a lifetime opportunity to research history first hand, something a lot of people do not get. I'm very thankful to Scotiabank, Air Canada, and The Vimy Foundation for allowing me to be a part of this wonderful program. Frankly, I'm also excited to meet new people again. COVID prevented me from doing that for all of my high school life, and now I get to meet like-minded individuals also interested in studying and preserving this history.

Q: Learning about Alexander's life, you have been able to put a name and a face to what is usually just a series of historical facts and dates for most Canadians. How has that experience been for you? Do you think it is important to get to know some of the people and their individual stories from these global events?

Uday: Dates, numbers and facts are important, but they do not tell the whole story. The First World War was caused by a bunch of petty grievances held by European heads of state, who were complacent and overly competitive. We tend to focus on their personal lives during the war, condemning most of the people involved to a fate of being a statistic to be mentioned in studies. By learning the stories of people such as Alec, we remember that even though the war was started by a few men, it consumed the lives of so many people. Not numbers, people.

Q: How do you feel about being able to represent Alexander and tell his story?

Uday: I see myself in Alec. I see a man who had a lot to say, loved his mother, and was a bit fatalistic at times. As a state-pacifist, I do not condone war. By sharing Alec's story, I hope to avoid the condemnation of another generation to his fate. It took me a while to understand, but life is beautiful. It's a shame that Alec's was thrown away. There are a lot of lessons to learn from him, however that one, the beauty of life, is the most important in my opinion and that's what I hope my audience takes away.

Q: What has been the most interesting thing you have learned from your research?

Uday: The most interesting I learned was probably the unmentioned story of the colonies in the War. Alongside my presentation about Alec, I'm giving a presentation about colonial forces in the war as well. The sheer amount of resources, labour and fighters that were expropriated from these countries is shocking, and due to Eurocentrism they are barely mentioned.

Q: What has drawn you to learning about this history? Why are you enthusiastic about learning more about these world changing events?

Uday: I think the answer to this lies in your question—it was world changing. I'm interested in all of history, the time and place doesn't matter. But, the First World War was such a monumental event that it really does deserve special attention. Our world today is still experiencing its effects, from all perspectives, technological, political, etc.

Q: Any other details or anecdotes you wish to share?

Uday: Once again, I do not condone war. Neither I nor The Vimy Foundation are attempting to glorify it through the VPA. We are merely acknowledging its importance to both Canada and the world at large, and I sincerely hope that humanity comes to the realization that peace is invaluable, because peace means life, and life is the most beautiful thing in the universe.

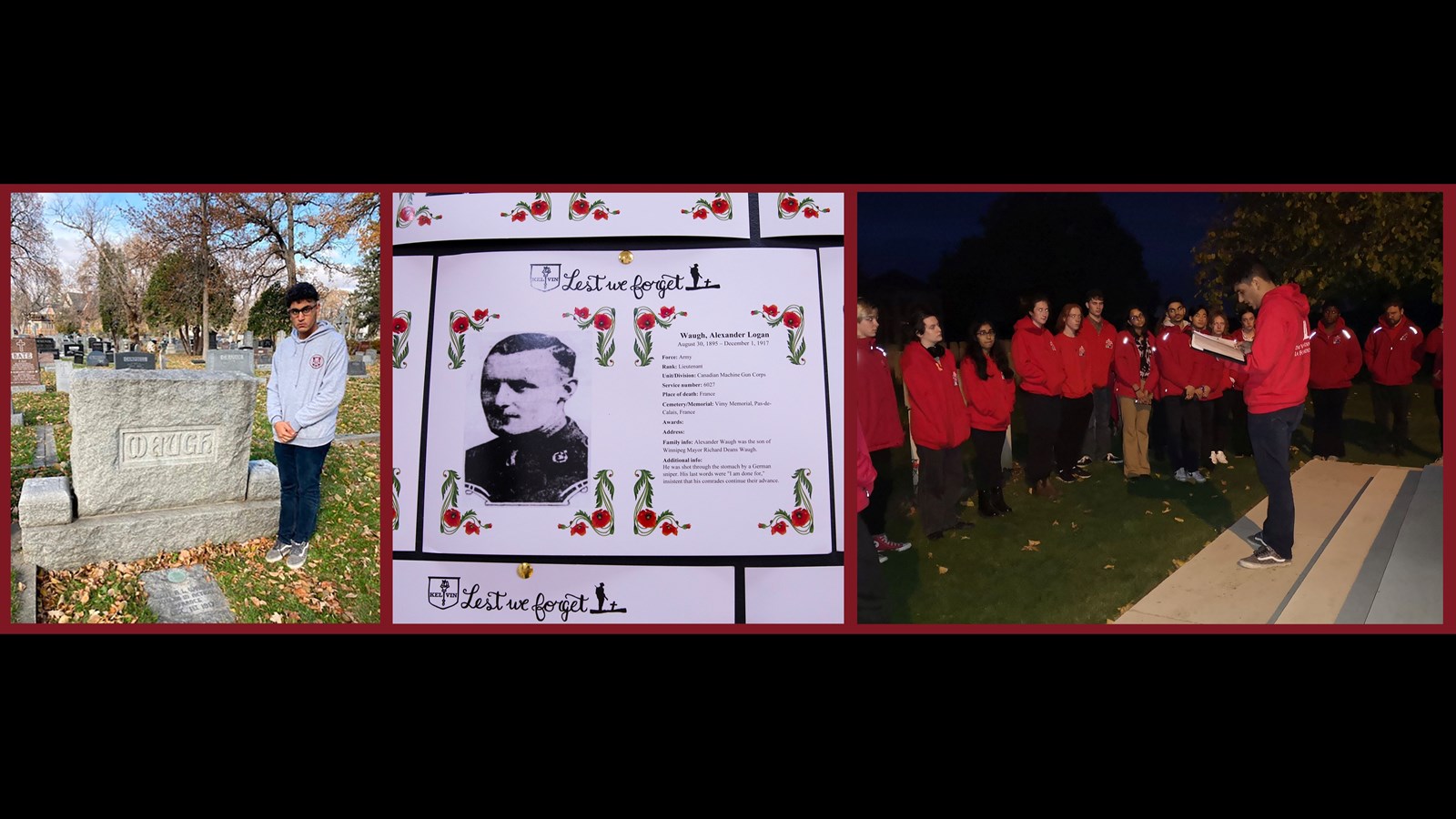

Uday presenting near where Alexander Waugh was killed. Supplied photo.

Uday presenting near where Alexander Waugh was killed. Supplied photo.

•••

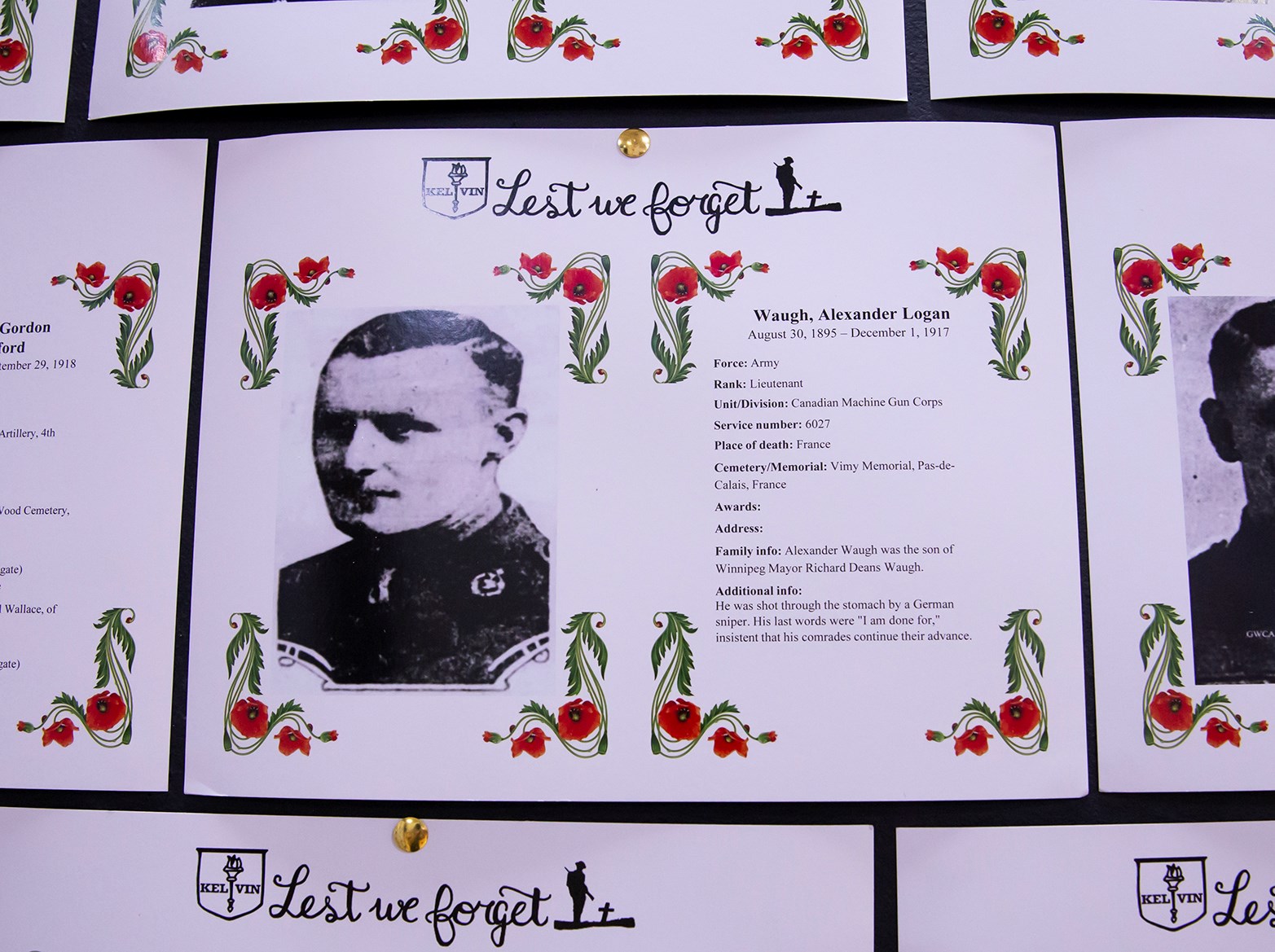

Here is a copy of Uday's presentation on Alexander Logan Waugh, as delivered in France in Nov. 2022.

Lt. Alexander Logan Waugh

By Uday Bhardwaj

Lieutenant Alexander Logan Waugh was a man of several names- “Alec”, “Al”, “Pinkie”, and many more. The fact remains however, that he did not have to fight. He came from a very wealthy and well-connected family. His father, Richard Deans Waugh ran a successful real estate firm and was Mayor of Winnipeg in 1912, 1915 and 1916.

Nevertheless, he still followed in the footsteps of his brother Richard Douglas Waugh who had gone overseas with the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1914, and joined Lord Strathcona’s Horse after leaving Kelvin High School, my high school. Due to his father’s political connections, he was able to secure a promotion to Lieutenant quite easily and quickly.

He was a member of the Canadian Cavalry Corps, specifically the Machine Gun Squadron. He served with Canadian, British and Indian troops, and fought in perhaps one of the bloodiest battles of the war- the Battle of the Somme. The war was not easy for him. He wrote a letter to his father on the 28th of November,1917, while serving in the Battle of Cambrai. He details his miserable life in the trenches, and says “for a few minutes, Dad, I looked at the finish and it didn’t seem so bad going out with the knowledge that I had done my best. I didn’t think of you or mother. The only things were the guns and their safety…”. Later on in the letter he says “We go into the trenches in a few days. I am fit as a fiddle, thankful to be alive, and very tired...”

Three days later, on December 1st, 1917, Alec Waugh was shot by a German sniper.

His father was distraught and searched far and near for his body. He even used his position as diplomat to gain access to the battlefields, but had no luck. Until one day, he received a letter from one Ed Large, who served under Alec. He told Richard where to find the body as he had been one of the two soldiers who buried him (corroborated by Al’s death report). However, still no luck. Richard Deans Waugh gave up. He said, in a letter to Mr. Large, that “We are reconciled to the fact that his grave will remain among the thousands undiscovered”.

Uday at the Waugh Memorial at St. John's Cathedral, Winnipeg. Supplied photo.

Uday at the Waugh Memorial at St. John's Cathedral, Winnipeg. Supplied photo.

He resigned to creating a memorial to his son at St. John’s Cathedral in Point Douglas, Winnipeg, which I visited. However, through Richard Waugh’s personal notes and correspondence with several people, including Ed Large, I was able to track down the rough location of Alec Waugh’s death—on a hill just southwest of where we are standing, Villers Hill British Cemetery. This cemetery has 350 unidentified bodies buried here, and it's very likely that Alec Waugh is one of them as it is the closest cemetery to where he was originally buried. 4 identified members of Lord Strathcona’s Horse who served with Alec are also buried here, and they died on the same day as him, December 1st, 1917. This further solidifies my theory, however, it's impossible to know for sure where a 105-year-old body is.

It’s bizarre to think that a man from my school, about the same age as me, lived through so much. We both shared a common passion as well- writing. I, for prose, but he, for poetry. He wrote a poem to his mother, entitled “Mother Mine”, that was published in the Winnipeg Free Press and a copy of it set to sheet music exists in the American Library of Congress today. I’d like to read this poem but before I do, I ask you all to just take a moment and reflect on Al’s life. Personally, I see myself in him—a man who loved his mother, had something to say, but I will be able to explore my passions. He will not.

Mother Mine

by Lt. Alexander Logan Waugh

Cross the threshold of the night

It comes, a memory,

The little loves of baby days,

The loves of yet to be;

Personified in saintly grace

With haloed love divine

She stoops to kiss me,

Ere I sleep,

This little mother mine

Throughout the greying dawns and dusks

A thousand shadowed fears are stilled

By steadfast mother love,

A burden of the years

Is lifted from a longing heart

And with my hand in thine

there is no fear

The light has come,

Has come with you

Sweet mother mine

Should my country, Canada, ask for all I have,

That I will gladly give

My hopes, ambitions, yea my life

that freedom still may live;

And when life’s light is fading fast

And first bright star shells shine,

I’ll tell this story o’er again,

I love you mother mine.

•••

On Nov. 10, Kelvin teacher Christopher Young had the chance to tell students more about Waugh’s life during advance Remembrance Day services. Here is the full text of Mr. Young’s speech.

Teacher Christopher Young tells Alexander Waugh's story to Kelvin students and staff, Nov. 10, 2022.

Teacher Christopher Young tells Alexander Waugh's story to Kelvin students and staff, Nov. 10, 2022.

Remembering Alex Logan Waugh

By Christopher Young, teacher, Kelvin High School

A few weeks ago, students in the Kelvin History Club visited St. John’s Anglican Church in Winnipeg’s North End. They explored the church’s majestic interior with its beautiful stained glass windows, some that remember our country’s military history. Outside, they wandered through its cemetery, covered by autumn leaves, where several of Winnipeg’s well-known citizens lie. On the cemetery’s southern edge is a memorial stone that commemorates the life of a soldier named Alex Waugh who was killed in France during the First World War. Our club hoped to see the stone because Grade 12 student Uday Bhardwaj had researched Alex’s life in preparation for his Vimy Pilgrimage trip- a ten-day national educational program to visit First World War Canadian battlefields in France and Belgium. Uday was interested in the soldier’s story because he was from Winnipeg, he was the son of our city’s mayor, and most significantly he went to Kelvin.

Alex studied at Kelvin when it opened its doors for the first time in 1912. He was a gifted and passionate writer who worked for the school newspaper. When the war broke out in 1914, inspired by his older brother Doug’s enlistment, Alex signed up with the Lord Strathcona’s Horse regiment. At Camp Sewell, a military training facility near Brandon, Alex developed close friendships with other regimental soldiers. In a letter to his dad, Alex wrote, “Yesterday night we sang songs, wrote letters and finally wound up around the big open fire. Occasionally our thoughts will all turn together across the seas. It is on these occasions that we bring out the now well-worn pictures of the best little mother in the world…or pictures of our sweethearts, if we have one. It is this mutual trust and interest in each other that makes me so loyal to my squadron.”

In 1915, Alex was finishing his training in England and he had been promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. He missed his family profoundly, he wrote to his dad, “someday I shall see you and mother, with Doug, safe at home….broken and crippled perhaps, but happy knowing that we fought for our home, our mothers, sisters and sweethearts, and the world is right again.” By 1917, Alex was a hardened soldier who had survived over a year fighting in the deadly trenches on the Western Front. He commanded a machine gun squadron and he was a popular leader known for taking good care of his troops. In November, he and his regiment prepared for an upcoming offensive near the town of Cambrai in northern France. Nervous about the battle, he wrote home, “If I should die, remember that I gave gladly all I had to keep a smile on your lips and sorrow from your hearts. I am only one of the millions who are to know the bitterness, the aching heart and when the finish comes, the longing for some last kiss or touch of a hand and a voice to say, “well done my son”.

A few days after he wrote this letter, Alex was killed when he was shot in the stomach by a German sniper. In his last conscious moment, he yelled “I am done for” and told his men not to help, in order to keep them safe and out of the line of fire. Alex was 22 years old.

When the war ended, Alex’s dad traveled to France on multiple trips in an effort to find his son’s grave, without success. In a letter to a soldier who served under Alex, Waugh explained, “Naturally we would like to find him but, after all, it does not matter much. He died and was buried where he did his duty like tens of thousands of other young Canadians whose graves will never be located.”

On Tuesday, standing close to where Alex was killed, Uday presented the soldier’s life to 19 high school students from across Canada. He told the group that Alex was one of over 20,000 Canadian First World War soldiers with no known grave, one of 11,285 names commemorated on the Vimy memorial in France, and one of the 55 Kelvin soldiers who died during the war. BUT most importantly, he shared with them some of the stories about Alex that you have heard today and he expressed that he had developed a real bond with him, particularly regarding their common talent and love for writing.

Remembrance Day is an opportunity for us to make authentic connections with soldiers from the past like Alex Waugh. To recognize their enormous service and sacrifice by remembering them not just as numbers but as real people, with real lives, real feelings and real families. Families who grieved the loss of their loved ones, who searched for their graves overseas and who erected modest memorial stones in Winnipeg churchyards, thousands of kilometers away from the battlefields, to do their best to commemorate their child’s life. They were determined to honour the memory of their loved ones - for in a way - to preserve their memory was ultimately to bring them back to life. But over time many of the families have passed away, and so it is NOW our duty to the dead -largely through stories- to continue this legacy. It seems to me it is the least we can do.