WSD students dig the past

April 24, 2024 News Story

WSD students had a blast explaining the past at the Historical Thinking Symposium.

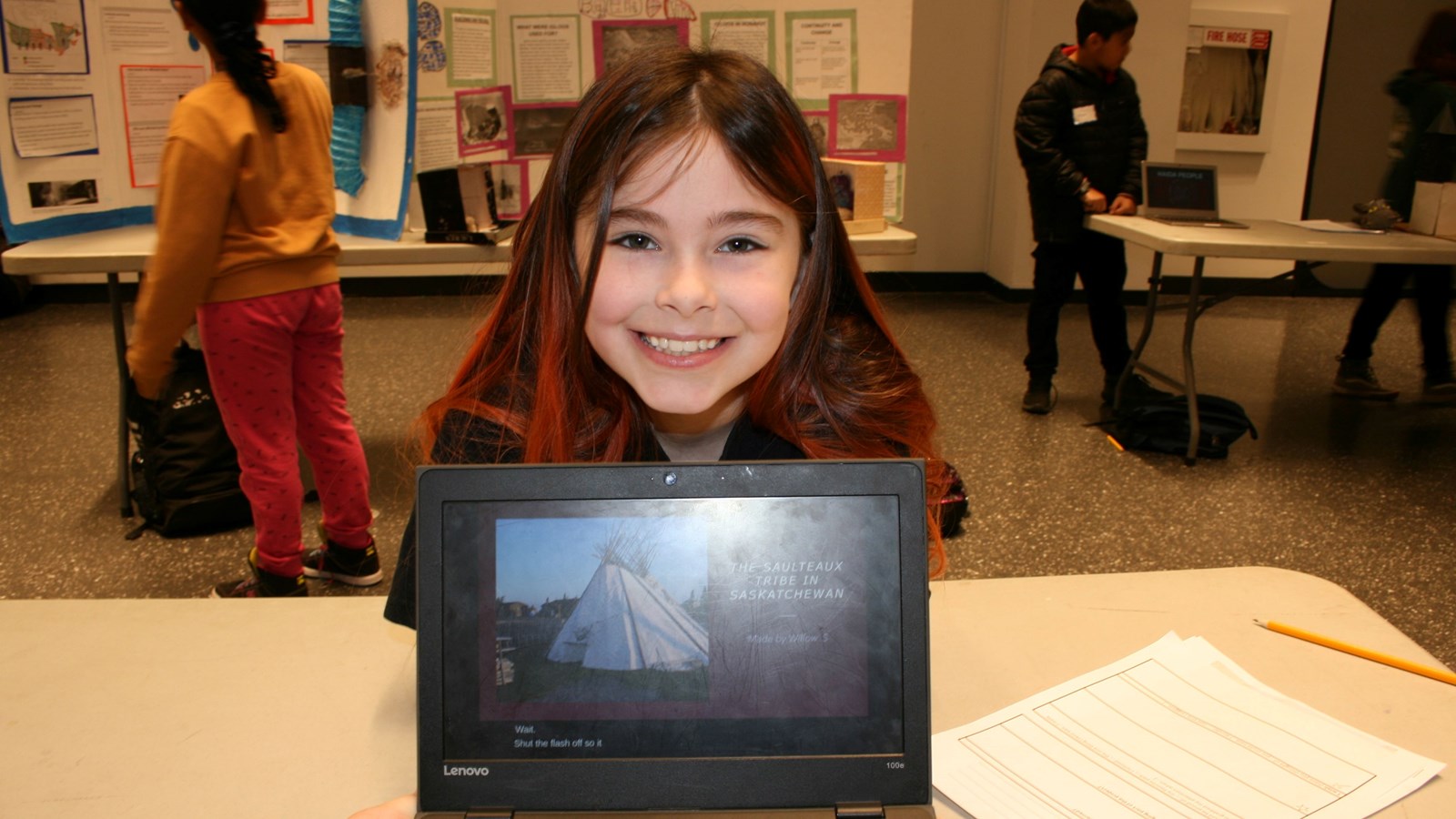

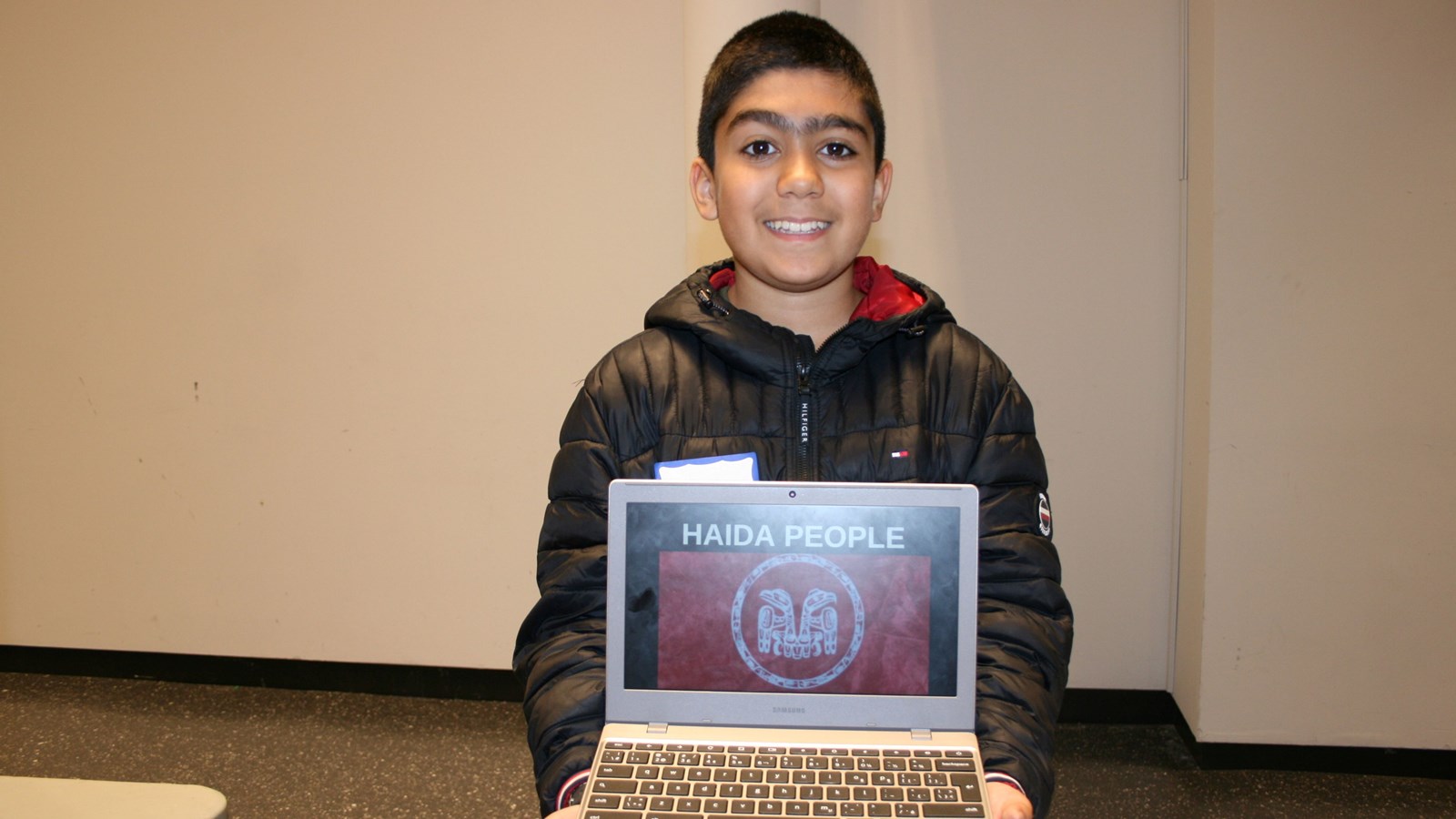

Students from Sargent Park School, Fort Rouge School, Gladstone School and École Robert H. Smith School held a heritage fair at the Manitoba Museum on April 23.

Approximately 100 students presented historical thinking projects at the symposium. The projects, mostly delivered on traditional backboards, covered such topics as Nova Scotia civil and women’s rights activist Viola Desmond and the two-decade long water crisis on Shoal Lake 40 First Nation.

“It's like a science fair, but for history,” said Clara Kusumoto, a professional support services teacher.

“I work with four schools and 12 teachers on historical thinking concepts, so learning about inquiry and critical thinking, historical significance, evidence, and continuity and change. We’ve been working all year on these concepts in class and doing supporting lessons and it has culminated in this event, a showcase of the student’s learning.”

Sargent Park Grade 9 students Christen and Selena presented a project titled Tragedies of the Japanese Internment. The project explored the forced displacement and confinement of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War.

In the wake of the Japanese Navy Air Service military strike on Pearl Harbor, the Canadian government forced over 20,000 Japanese Canadians from their homes and livelihoods in British Columbia, despite lacking proof of any acts of sabotage or espionage.

“Manitoba and Alberta opened up beet farms and that’s where they had to do forced labour,” Christen said.

“I didn’t even know this was a thing. I knew a little about the Second World War, but I didn't know this was going on during the same time period. It’s really shocking, because you think Canada is so great, especially in regard to accepting immigrants.”

Canada has since acknowledged and apologized for the wrongs it committed against Japanese Canadians.

“There was a formal apology in 1988,” Selena said. “When Brian Mulroney, the prime minister at the time, and Art Miki, the president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians, signed an agreement to give $21,000 compensation to every single Japanese Canadian survivor that went through the internment.”

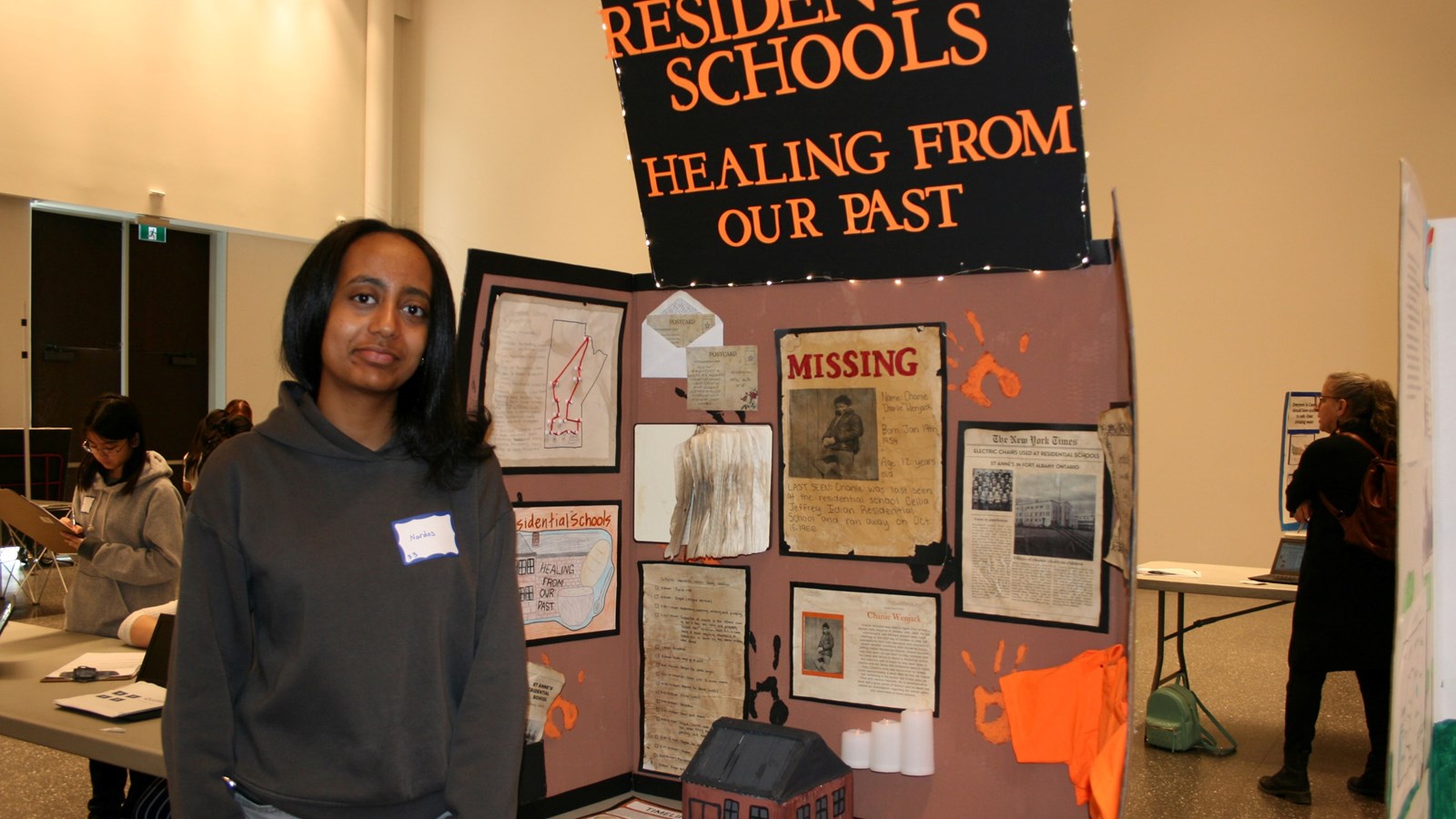

Another dark chapter in Canada’s past that is only now being reconciled is the Canadian residential school system. Grade 9 Sargent Park student Nardos and her classmate crafted a project titled Residential Schools: Healing from our Past.

“We thought it would be good to do a project on residential schools because I feel like people hear things like Orange Shirt Day or Truth and Reconciliation, but they don’t actually understand what they’re hearing about,” Nardos said.

Nardos and her partner used The Canadian Encyclopedia, the book I Am Not a Number by Jenny Kay Dupuis and Kathy Kacer, and CBC Archives to research the residential school system and its many atrocities, as well as the continued impact of residential schools on survivors and their descendants.

“We learned about something called intergenerational trauma,” Nardos said. “Even though residential schools ended years ago, it still affects Indigenous people and communities today.”

Just in time for the NHL playoffs, Robert H. Smith students Declan and Tenoch crafted a project titled Canadian Hockey History. The display detailed how the game of hockey started, how hockey equipment has changed over the years, and the extraordinary on-ice feats of hockey legends like Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux.

“Some people think hockey started in 1875 in Montreal, but others say it was played in Nova Scotia by the Mi'kmaq people who played with a stick and a wooden block,” Tenoch said.

“The evolution of hockey is so interesting,” Declan said.

“They used to use a ball instead of a puck,” Tenoch added.

“And sometimes it was made of poop. Frozen cow poop,” Declan said with a laugh.

Whatever history the students choose to look into, Kusumoto said the idea is to do it with a critical lens.

“We know this person, place or thing is historically significant but why is it historically significant? What’s changed? What has remained the same?” Kusumoto said.

“Getting the kids to investigate and do their own research and using their own ideas to connect to that research, it doesn’t end up being just a regurgitation of information. They’re analyzing and deeply thinking about history.”