Grant Park students get first-hand account of residential schools

April 19, 2021

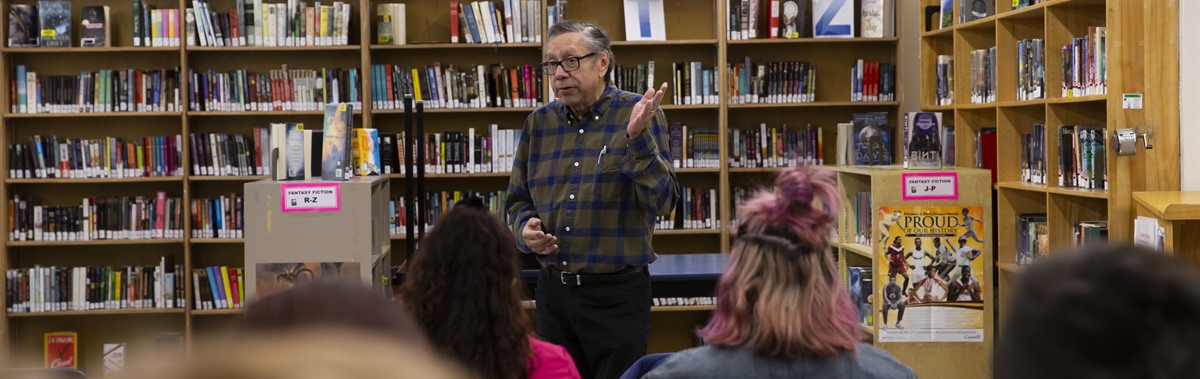

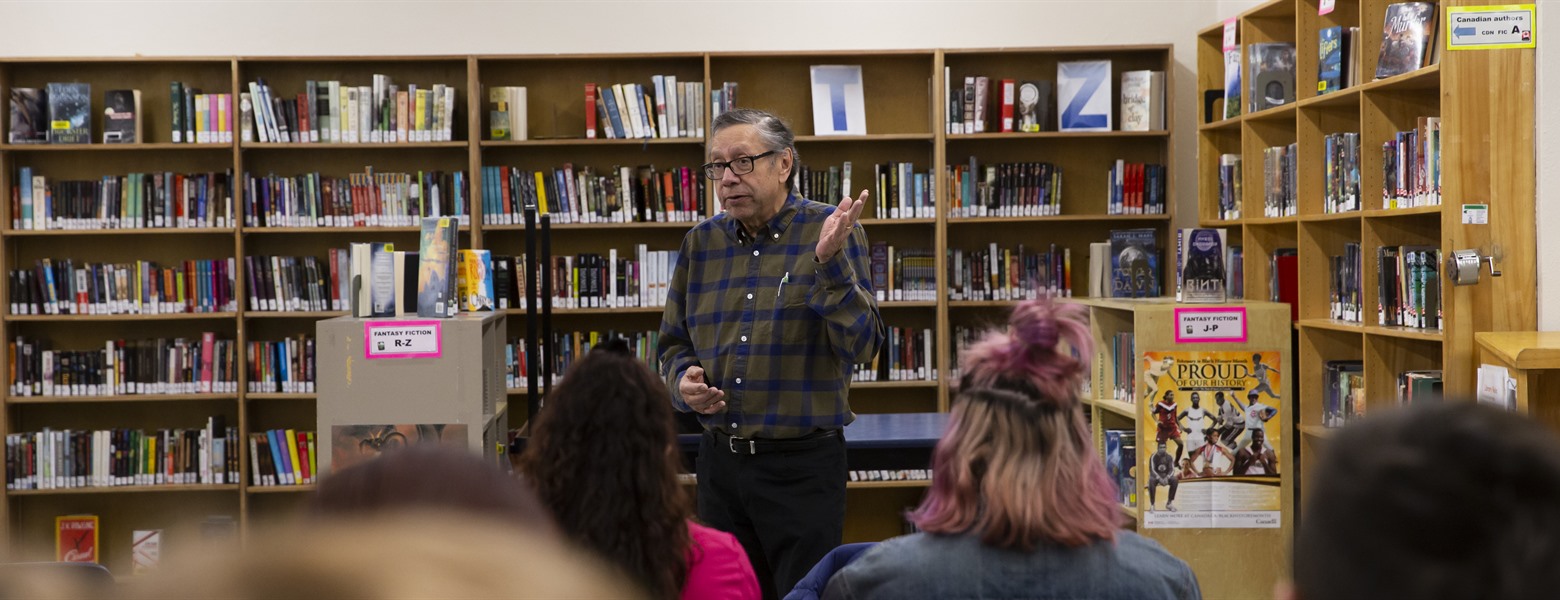

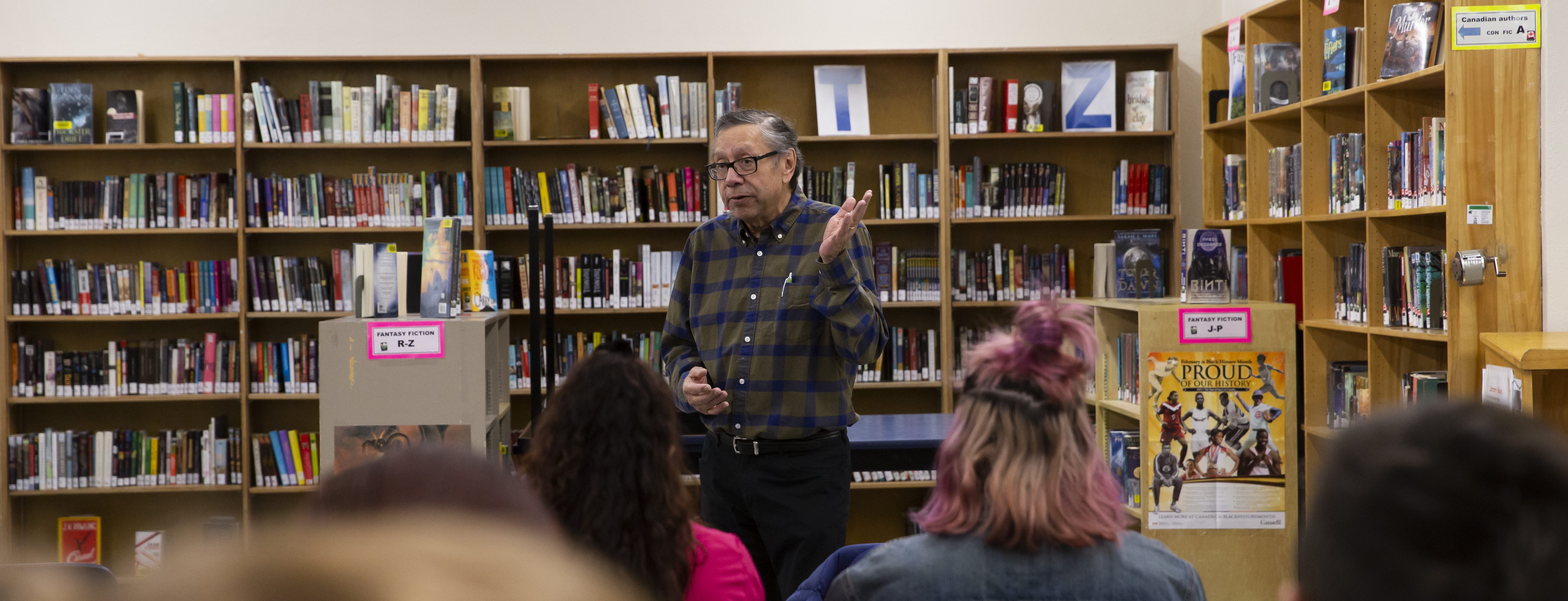

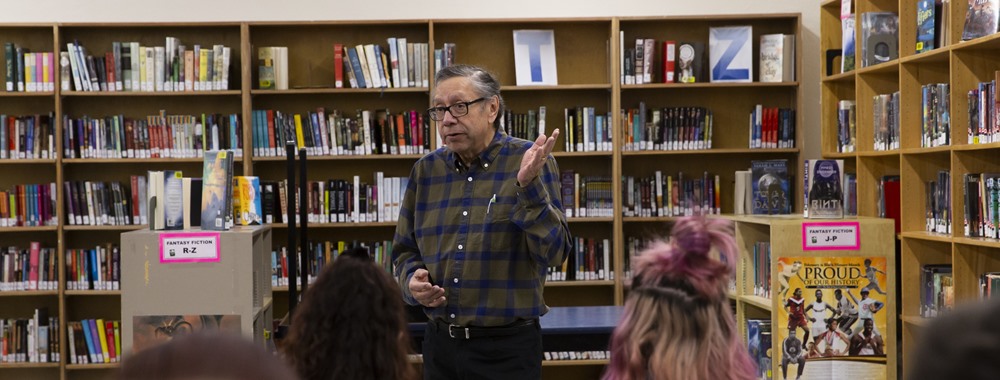

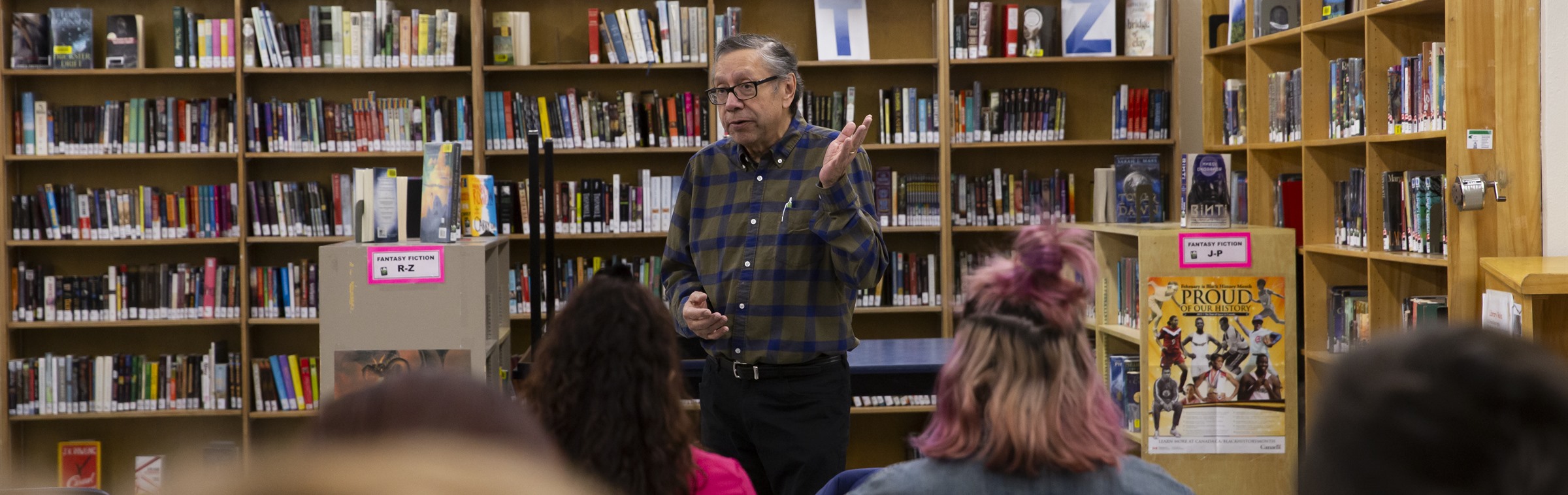

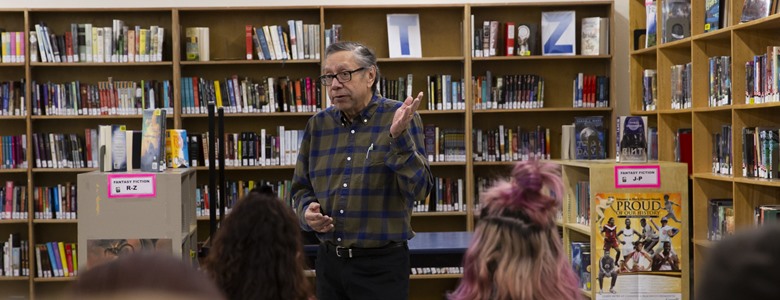

Grant Park High School students recently had an opportunity to hear the first-hand experiences of a residential school survivor, as well as take part in a virtual tour of a residential school, as part of a new pilot program called Embodying Empathy.

Before taking part in the virtual reality tour, students met Dave Rundle, who attended Fort Alexander Indian Residential School (which operated from 1906 to 1970). Mr. Rundle has been speaking about his experiences to different audiences for the past two years.

Mr. Rundle doesn't remember every detail of residential school life. But bits and pieces stand out. Some are seemingly random fragments, like getting a slice of bread and a piece of lard before supper. The students would make bets and use their lard for wagers.

Another is a pillow fight in the dormitory, when the students had a moment away from the watchful eyes of the nuns.

"We were running and jumping from bed to bed and feathers were flying everywhere," said Mr. Rundle, who originally hails from Ebb and Flow First Nation. "In those days, the pillows were filled with goose feathers. Can you imagine that…30 little guys, some had broken pillows…that was a good time. We were jumping and laughing…that lasted maybe ten minutes. Next thing we know, the door opens and a nun is standing there. Of course, we all scattered."

Other memories aren't as pleasant, and leave deeper cuts on the psyche.

Mr. Rundle is quick to point out that not all of the nuns and priests who worked at the school were abusive.

"The sexual abuse…I don't want to go into detail about it other than to tell you it happened. It happened not only to me, but to a lot of other boys and girls," he told students. "I know of two nuns that committed sexual abuse with boys and girls, and I know of one priest who committed sexual abuse of other boys. That to me was the most demeaning, horrific experience. Sometimes people ask me 'You were in residential school 60 years ago…can't you get over it?' How can you? For anybody who has experienced abuse in their lives, you know. You can't, no matter how long ago it happened.

"One of the toughest things, after that occurred, was wondering when the next time would be. The next time did happen. I'll just leave that to history."

Other forms of abuse were more regimented into the residential school system.

"Whenever you had a fight with another student…you were made to put on boxing gloves after you had the initial fight. And you fought again until somebody gave up. What I found interesting, when I first saw that happen, is that both boys were crying. And I couldn't figure out why the winner was crying…I never knew until it happened to myself. I had three fights…I lost two and won one. The fight that I won, I was crying like the other kid did…you felt so mad, so lonely, so helpless and frustrated because there was nothing you could do."

Along with suffering abuse, another emotion that was constant during his five years at residential school was the feeling of loneliness.

"My brother and I were in residential school ten months of the year…we rarely saw our parents. We didn't get to go home at Christmas, Easter or weekends. My parents were living in Winnipeg at the time and they couldn't afford to come out to pick us up."

Those long separations caused many residential school families to break down.

"You became hardened from caring for other people. You didn't know how to…that's just the way you grew up. There was a loss of family attachments, there was the loss of parenting. There was a loss of home cooking. There was a loss of sharing birthdays, and extended family. There were so many home things that were lost."

The Indigenous culture itself was perhaps one of the most common casualties of the residential school system.

"There's low self-esteem because of the way you were punished. You were called savage and you weren't allowed to speak your own language. You weren't allowed to practise your culture. You weren't allowed to practise your own spirituality. You had to pray the way you were told to pray…as a Catholic. You develop an inferiority complex, like you are so much less than anybody else."

Two years after leaving residential school, both of Mr. Rundle's parents had passed away. His grandmother raised him the rest of the way, into adulthood.

"I had a grandmother who was very good, a very strong person. She had family values and you had to live with those values," he said. "She raised 11 of us."

"Reconciliation to me, is a one-on-one thing. For students, when you meet someone of a different colour or race, just say hi. Just acknowledge them—that means a lot."

The fallout of the residential school system has taken many forms over the years amongst those who lived through the experience.

"There weren't any mental health services for survivors, and a lot of them don't know what to ask for," Mr. Rundle said.

"Some were so affected that they took to alcohol, some were affected so badly they committed suicide. Some lost their parents, some lost children…because they tried to discipline their children the way they were disciplined in residential school. It was not an easy transition."

Mr. Rundle sought alcohol as a way to forget.

"I started using alcohol when I was 17, I started smoking cigarettes around the same time. I drank for 20 years. I was not a violent person…my wife was understanding, she could put up with my drinking. I never hit her and I never harmed my children. She was strong."

Today, Mr. Rundle is clean and sober. But there are still reminders of his years at Fort Alexander Indian Residential School. Sometimes he'll see other residential school survivors on television and they'll also speak of the loneliness and all that was lost.

"Years and years later, something clicks and it reminds you what happened."

For Mr. Rundle, Reconciliation has to be more than formal apologies and gestures; true Reconciliation will take place off-stage, away from politics.

"Our leadership, our politicians, they want reconciliation in such a grandiose way. And that just doesn't happen," he said. "Reconciliation is understanding the person beside you. Recognizing their culture, their language…and accepting them for who they are. It's like reconciling with your boyfriend or girlfriend. You talk about your differences, you talk about what went wrong. You can talk a bit about history, but we were not there when it happened. So to me, I accept you for who you are today."

He credits the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the testimonies of other survivors, with giving him the impetus to share his own experiences.

"Hearing the stories and other people talking about their experiences, it encouraged you to tell your story," Mr. Rundle said. "If the Truth and Reconciliation Commission didn't happen, I don't know if I would have come out with my story. It took a while. You feel embarrassed and ashamed by it…but it gets easier the more you talk about it."

The 73-year-old is retired after working for many years with the Department of Indian Affairs, and his wife still works as a nurse in rural Manitoba; they have three adult children.

"They're all out living on their own and they're doing well," he said. "But you'll always be a parent, I don't care how old your children are."

Deeply affected

Grade 11 student Madlin Murad, who came to Canada as a refugee from Iraq, said Mr. Rundle's presentation affected her deeply. Madlin, who practises the Yazidi religion with her family, faced persecution from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant before coming to Canada.

"I'm also a survivor of a genocide," she said. "We were attacked by Islamic State just because of our religion and who we were."

She said she was saddened by Mr. Rundle's experiences, and those of other residential school survivors.

"I was shocked to hear this. When I was back in Iraq, you hear that (Canada) is a country of human rights and nothing like this would happen."

Virtual tour

Following Mr. Rundle's presentation, students had the opportunity to try out a virtual recreation of a residential school.

Embodying Empathy is a 3D "storyworld" that is based on Fort Alexander Indian Residential School. The program was developed with input from residential school survivors, educators and programmers.

"The tech people and designers got a lot of information from the survivors, and pretty much built the world from that," said Andrew Woolford, a Professor of Sociology and Criminology at the University of Manitoba. "When they built it, the survivors had a look and would correct them if something was wrong."

For scheduling purposes, students got an abbreviated virtual tour; they were able to walk to the school and see its exterior, then morph from room to room while they hear what survivors experienced in each room.

"They'll be able to get a sense of that space and have the survivors' stories become more real," Mr. Woolford said. "It's just like if you've ever had a chance to travel through Europe and see some of the concentration camps, those sites and memory can really evoke what happened. We don't pretend to put them into the experiences of the survivor. This technology can approach that, but it can't get that close. You'll never fully feel what the survivor felt, but you'll get closer to a better sense in that way."

Developers studied the reactions of university students to the tour and saw the immersive experience did generate empathy. Approximately 300 university students have taken the tour so far, along with roughly 120 high school students.

"The studies we've conducted at the Psychology Lab at the University of Manitoba so far, in general students are showing higher levels of empathy having been exposed to the virtual world, versus being exposed to the comparison case," Mr. Woolford said. "They've also shown a greater knowledge of residential schools through this experience. It allows a different type of learning than simply reading or watching videos."

While developers are not collecting data from the high school viewing sessions, they are taking feedback from students as to how to improve the tour.

"Technology is always getting better, and these students are often quite tech savvy," Mr. Woolford said.